INTRODUCTION

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a benign chronic disorder which is uncommon in children. The exact mechanism of SRUS in children is unknown but it is thought that due to dyssynergic defecation, anterior rectal mucosa prolapses which causes ischemic injury as well as repeated self- digitation also causes local trauma and ultimately rectal ulcer.1 The diagnosis of SRUS is established on symptomatology and endoscopic findings. Major clinical features include rectal bleeding, mucoid rectal discharge, straining during defecation, tenesmus, perineal and abdominal pain, constipation, and proctalgia,2 although one-fourth may remain symptom-free.2 Colonoscopy with characteristic features on histopathology is essential for the diagnosis of SRUS. In children the most frequently used medical treatment is the topical application of sucralfate and mesalamine.2

As SRUS is a misdiagnosed disorder and symptoms mimic inflammatory bowel disease, a high level of suspicion is needed for diagnosis in children. We here report a teenager who presented with rectal bleeding and was finally diagnosed with SRUS.

LEARNING POINTS

1. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome is a rare entity in the paediatric age group, which requires a high index of suspicion.

2. Colonoscopy with histopathology should be done to diagnose solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

3. Topical application of sucralfate and mesalamine along with laxative proved to be an effective treatment.

CASE DESCRIPTION AND MANAGEMENT

A 14-year-old girl came to the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) with a 5-month history of rectal bleeding. The bleeding was bright red, small in quantity, and occurred during defecation, often accompanied by tenesmus. She also experienced straining during defecation and occasional constipation, sometimes requiring digital disimpaction of stool. She had no fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, joint pain, or history of tuberculosis or blood transfusions.

On physical examination, she was found mildly pale, and afebrile, with no lymphadenopathy, BCG mark present, and no evidence of oral ulceration. A digital rectal examination revealed no abnormality. Anthropometrically she was well thrived. Inflammatory bowel disease, rectal tuberculosis, and colonic polyp were considered differential diagnoses.

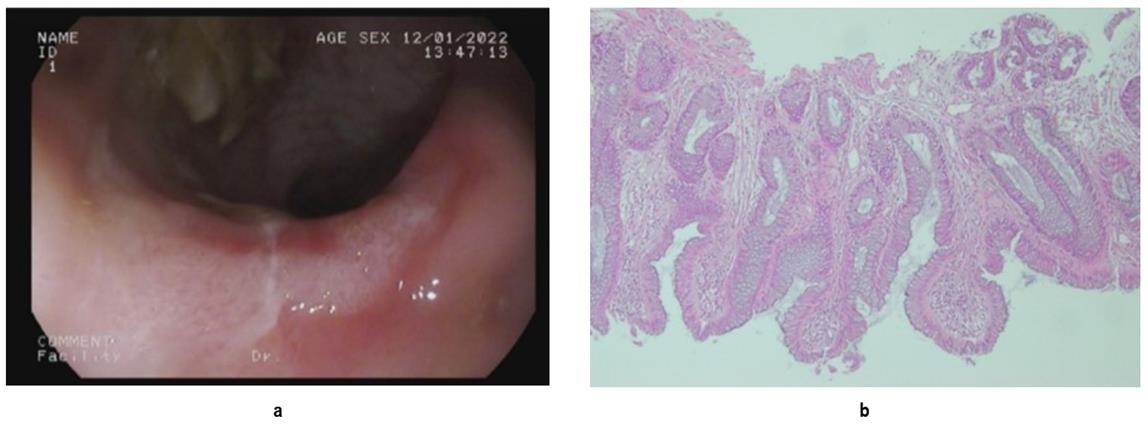

Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, Mantoux test, and abdominal X-ray, showed no abnormalities. A colonoscopy revealed a single erythematous lesion with exudation located 8-10 cm from the anus. Histopathology report from the affected area showed a focal ulcerated area lined by glandular tissue with fibromuscular obliteration of lamina propria. Diamond-shaped glands and a few strips of smooth muscle fibres are seen in between the crypts (FIGURE 1). Based on clinical features and colonoscopy findings with histopathological report, we reached the final diagnosis of SRUS.

The child was reassured and counselled and advised to avoid straining during defecation and take a high-fibre diet. The child was prescribed stool softeners along with topical mesalamine at a dose of 60 mg/kg and sucralfate at 50 mg/kg for 6 weeks.2 After a few days, the patient improved clinically. On follow-up after 6 weeks, symptoms completely subsided. Repeat colonoscopy could not be done because the guardian of the patient did not agree. On one-year follow-up, there was no recurrence of symptoms.

DISCUSSION

After SRUS is often unrecognized in children. A limited number of case reports and series have been published in children. Similar to our patient, fresh rectal bleeding, mucorrhea, tenesmus, constipation and excessive straining are the major symptoms.3, 4 Histopathology is the "gold standard" in the diagnosis of SRUS.5 The typical colonoscopy finding is shallow ulceration on an erythematous adjacent mucosa located on the anterior rectal wall at 5 to 10 cm about the anal verge.2 However, SRUS is a disease of misnomer as the lesion can be multiple instead of being solitary, rather than being ulcerative, the lesion may be polypoid or hyperaemic and it may not involve the rectum.2 In our patient, the lesion was erythematous with exudation, single in number, involving the rectum.

Our patient had typical histopathological characteristic fibromuscular obliteration of lamina propria.5 There is no unified treatment guideline for SRUS. Suggested treatment of SRUS includes reassurance of patients, high fibre diet with stool softeners and avoidance of straining. If patients fail to respond to conservative treatment, various topical drugs such as sucralfate, mesalamine, and corticosteroids should be tried.5 Sucralfate enema was found to be effective in relieving symptoms in 58.3% of cases. Though the long-term success rate of mesalamine is controversial, 41.7% of patients responded to local mesalamine in a study conducted among 140 cases of SRUS.5 Our patient responded to topical mesalamine and sucralfate along with laxatives. Therefore, surgery was not indicative.6

In conclusion, SRUS should be kept in mind if a child presents with prolonged rectal bleeding. Routine colonoscopy and histological examination should be done early in all children who present with prolonged rectal bleeding.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank Dr. Sutupa Halder Supti, MD resident of the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, BSMMU for her assistance and the patient who participated in this study.

Author contributions

Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: WM, FB, MR. Manuscript drafting and revising it critically: NM, FB. Approval of the final version of the manuscript: NM, WM. Guarantor of accuracy and integrity of the work: NM.

Funding

We did not receive any funding for this case report.

Conflicts of interest

We do not have any conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not sought because this is a case report. However, informed written consent was obtained from the patient for preparation of this manuscript and publishing her pictures.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

1. Forootan M, Darvishi M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 May;97(18):e0565. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000010565.

2. Dehghani SM, Malekpour A, Haghighat M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children: a literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Dec 7;18(45):6541-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6541.

3. Blackburn C, McDermott M, Bourke B. Clinical presentation of and outcome for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Feb;54(2):263-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31823014c0.

4. Dehghani SM, Bahmanyar M, Geramizadeh B, Alizadeh A, Haghighat M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: Is it really a rare condition in children? World J Clin Pediatr. 2016 Aug 8;5(3):343-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i3.343.

5. Poddar U, Yachha SK, Krishnani N, Kumari N, Srivastava A, Sen Sarma M. Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome in Children: A Report of 140 Cases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020 Jul;71(1):29-33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000002680.

6. Suresh N, Ganesh R, Sathiyasekaran M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a case series. Indian Pediatr. 2010 Dec;47(12):1059-61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-010-0177-0.

|

|

|

FIGURE 1 (a) A single erythematous lesion with exudation has seen 8 cm from the anus; (b) Focal ulcerated area lined by glandular tissue with fibromuscular obliteration of lamina propria seen in the affected area. |

(c) 2024 The Authors. Published by BSMMU Journal