Conversion disorder with psychogenic vomiting and

coexisting organic etiology in an adolescent: A case report

Authors

- Tanbir AhmedDepartment of Psychiatry, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0912-1196

- Sifat E SyedDepartment of Psychiatry, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladeshhttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-3075-0294

- Afsana Benta AnowarDepartment of Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health, Dhaka, Bangladesh

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-8797-8735 - Syeda Rawnak JahanDepartment of Psychiatry, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0634-5136 - Nahid Mahjabin MorshedDepartment of Psychiatry, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladeshhttps://orcid.org/0009-0005-2297-6156

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3329/bsmmuj.v18i2.79006Keywords

Downloads

Correspondence

Publication history

Handling editor

Reviewers

Funding

Ethical approval

Trial registration number

Copyright

Published by Bangabandhu Sheikh

Mujib Medical University

This case study examines an adolescent girl with persistent vomiting who, after diagnostic challenges, responded well to psychiatric intervention.

The findings of laboratory testing, such as a complete blood count, electrocardiogram, metabolic panel, and radiographic investigations (including barium swallow), were normal. Endoscopic assessment showed non-specific gastritis. Initial laboratory results showed low adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) (3.55 pg/ml) and basal cortisol (8.30 μg/dl), with cortisol levels rising to 9.5μg/dl one hour after ACTH injection. Other hormone reports were normal.

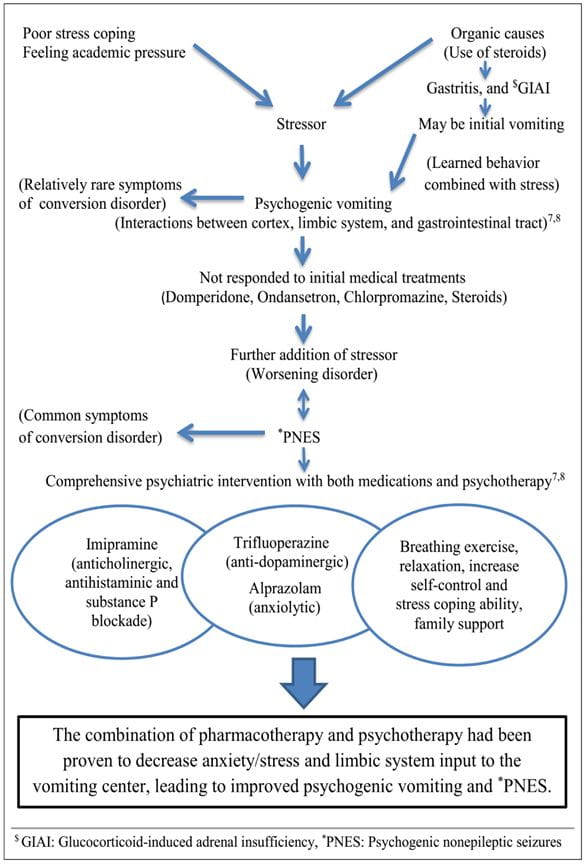

Glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency, which was discovered upon referral to endocrinology, was probably brought on by her previous use of steroids. The clinician initially ordered hydrocortisone injection; however, this was later changed to oral hydrocortisone. One month later, hydrocortisone was stopped when cortisol levels were 14.32 μg/dl. However, her vomiting persisted, and suddenly, within 24 days of admission, she developed frequent asynchronous limb movements without bladder or bowel involvement. Neurological evaluations identified psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). Symptomatic treatment offered no improvement.

Despite improvements in adrenal function and gastritis management, her symptoms worsened. This suggested that a complex psychological or functional component may be contributing.

A psychiatry consultation eventually diagnosed her with conversion disorder, presenting with a combination of symptoms according to DSM-5. Psychiatric assessment highlighted preoccupation with illness, feelings of helplessness, and moderate stress, with no significant family history of psychiatric disorders. She never self-induced the vomiting and thought her weight was ordinary. The treatment plan combined pharmacotherapy with supportive psychotherapy, relaxation techniques, stress management, and cognitive restructuring. Psychoeducation was provided to both the patient and her mother. No adverse events were reported during treatment.

After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s symptoms improved. She returned to full-time school attendance and demonstrated improved social interactions and emotional well-being. Follow-up sessions confirmed sustained symptom remission.

Categories | Number (%) |

Sex |

|

Male | 36 (60.0) |

Female | 24 (40.0) |

Age in yearsa | 8.8 (4.2) |

Education |

|

Pre-school | 20 (33.3) |

Elementary school | 24 (40.0) |

Junior high school | 16 (26.7) |

Cancer diagnoses |

|

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 33 (55) |

Retinoblastoma | 5 (8.3) |

Acute myeloid leukemia | 4 (6.7) |

Non-Hodgkins lymphoma | 4 (6.7) |

Osteosarcoma | 3 (5) |

Hepatoblastoma | 2 (3.3) |

Lymphoma | 2 (3.3) |

Neuroblastoma | 2 (3.3) |

Medulloblastoma | 1 (1.7) |

Neurofibroma | 1 (1.7) |

Ovarian tumour | 1 (1.7) |

Pancreatic cancer | 1 (1.7) |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 (1.7) |

aMean (standard deviation) | |

Categories | Number (%) |

Sex |

|

Male | 36 (60.0) |

Female | 24 (40.0) |

Age in yearsa | 8.8 (4.2) |

Education |

|

Pre-school | 20 (33.3) |

Elementary school | 24 (40.0) |

Junior high school | 16 (26.7) |

Cancer diagnoses |

|

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 33 (55) |

Retinoblastoma | 5 (8.3) |

Acute myeloid leukemia | 4 (6.7) |

Non-Hodgkins lymphoma | 4 (6.7) |

Osteosarcoma | 3 (5) |

Hepatoblastoma | 2 (3.3) |

Lymphoma | 2 (3.3) |

Neuroblastoma | 2 (3.3) |

Medulloblastoma | 1 (1.7) |

Neurofibroma | 1 (1.7) |

Ovarian tumour | 1 (1.7) |

Pancreatic cancer | 1 (1.7) |

Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 (1.7) |

aMean (standard deviation) | |

Pain level | Number (%) | P | ||

Pre | Post 1 | Post 2 | ||

Mean (SD)a pain score | 4.7 (1.9) | 2.7 (1.6) | 0.8 (1.1) | <0.001 |

Pain categories | ||||

No pain (0) | - | 1 (1.7) | 31 (51.7) | <0.001 |

Mild pain (1-3) | 15 (25.0) | 43 (70.0) | 27 (45.0) | |

Moderete pain (4-6) | 37 (61.7) | 15 (25.0) | 2 (3.3) | |

Severe pain (7-10) | 8 (13.3) | 2 (3.3) | - | |

aPain scores according to the visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10; SD indicates standard deviation | ||||

Psychogenic vomiting is typified by the following symptoms: nausea in generalized-anxiety disorder, habitual postprandial or irregular vomiting in MDD and mixed anxiety-depressive disorder, self-induced vomiting in obsessive-compulsive disorder, and continuous vomiting in conversion disorder [2, 4], as demonstrated here. The Rome-III criteria distinguishes it from persistent idiopathic nausea, and cyclical vomiting syndrome [1, 5]. Most of the group suffer from a serious mental illness, mainly conversion disorder or MDD [2, 6]. Previous studies align with the finding that psychogenic vomiting often manifests in adolescence and may involve academic stress, perfectionism, and emotional dysregulation [1, 6]. Some patients show more than just emotional difficulties. Vomiting can develop into a habit and be regarded as a learned behavior, even though it may start as an organic or functional problem [2] (Figure1) [7, 8]. Furthermore, since they may influence treatment choices, metabolic factors should be taken into account [5].

Corticosteroid therapy for asthma may have predisposed the patient to glucocorticoid-induced adrenal insufficiency, contributing to her initial vomiting [9]. This also links to the unstable connection between cognition, emotion, and motor control in PNES, which frequently associates with a range of psychological, psychiatric, and physical symptoms [10]. The interplay between these factors underscores the complex nature of the patient’s condition.